Our first full day at sea. Open skies. Ship pounding along at 18 knots. Like rhinestone cowboys (as Glen Campbell used to sing), we are on the way to our horizon.

But this is not some pleasure cruise; today the talking stopped and everybody began to focus on what lies ahead.

The shaping of Endurance22 began almost three years ago not long after our return to the UK from Endurance19. The ice had given us a good kicking and although we didn’t talk about it, I think we all felt a bit bloodied. Personally, I felt as if somebody had just walked all over me with crampons. But there was no point in feeling sorry for ourselves; we had to learn from our mistakes and come up with solutions, that meant new search systems and better methodologies. In all this we had one big advantage that we did not have before, and that was experience. We now understood the pack and the nature of the challenge it poses.

When we began the preparations for Endurance22 it consisted of just the four Trustees of the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust, John Shears of Shears Polar and a small group of French Engineers from Deep Ocean Search (DOS), led by Nico Vincent. I had known Nico for many years; he used to work for Comex, the pioneering French deep-diving company, whose founder, Henri Delauze, had been a sponsor of my early excavations in the 1980s. In broad terms, Nico’s brief was to represent the Trust in the production of the new underwater search vehicles, as well as to devise and manufacture their launch and recovery systems and, indeed, everything else that would be needed to conduct complex deep-water operations beneath the frozen pack, including the design of the augers and derricks that would be needed to drill through the ice.

The challenges we all faced, but especially Nico, where truly daunting. Time and again we had to scrap our plans and, quite literally, return to the drawing board. We used to all meet by zoom every week or two to review progress. I have lost count of how many times Nico presented us with a new or evolved sets of engineers’ drawings, but in the end he got us to where we are now, in time and on budget. And all this, it must be remembered, happened at the height of the Great Pandemic when supply-chains worldwide had broken down and businesses everywhere had ground to a halt because their staff had been laid-off at home. Things that had been simple were suddenly fiendishly difficult. My point is that, from beginning to end, this project was incredibly hard and demanding.

As I look back there is one indelible moment that occurred over a year ago and which hangs in my mind as if it were yesterday. We had reached an impasse. We were clean out of ideas on how to proceed and there was between us dead-air of the kind writers used to call a pregnant pause. It was then that Nico said something that seemed to crystallise everything. Something that was blindingly obvious but just had to be said. In perfect but heavily accented English, he looked his laptop square in the eye and said: ‘Gents, this really is a very very complicated project.’

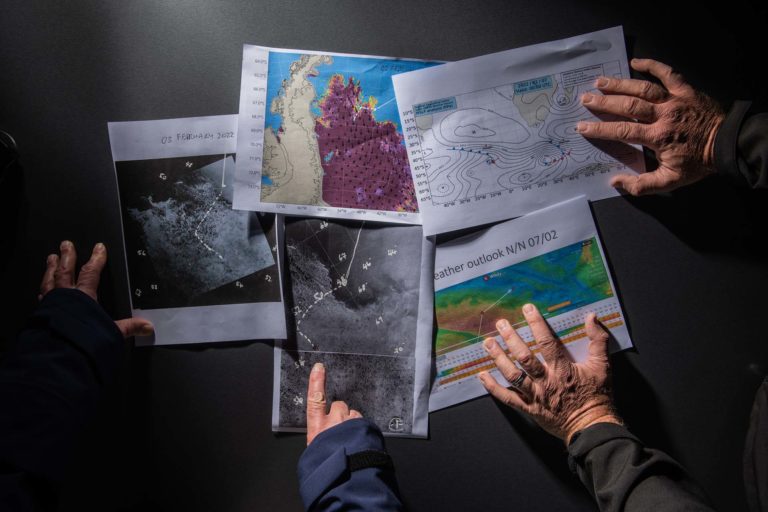

So, with that as preamble, let me come back to today. This afternoon there was a meeting in the ship’s auditorium during which Nico took us through every aspect of subsea operations. It lasted three and a half hours. There was nothing in his presentation with which I was not already familiar, but this was the first time I had seen it all rolled out in sequential order. What struck me was the sheer scale of what he had achieved, and, if we succeed in finding the Endurance, how indebted we will be to him and his colleagues in the South of France.

How do I feel now that we are at last on our way? On the one hand I am brimming with excitement; but, on the other, there is apprehension. All that has happened during the last 1075 days is now funnelling down at dizzying speed to a single result. Success or failure. It is completely binary; there is nothing in between. It is going to be either cheers and hallelujahs , or, once again, this whole thing is going to rise up and bite me in the bum.

By the bye, those crampons I spoke of. What I really picture in my mind’s eye as I write, are those studded boots that Chippy McNish made for Shackleton from screws taken from the James Caird when the Boss was about to commence his epic trek across South Georgia.

Mensun Bound (Director of Exploration)