And so with bands playing, drums beating, banners flying and every dog in Cape Town barking, we are – chin forward – on our way.

Soon after 9 am we slipped our lines and eased out into the steam. After all the press we received yesterday I thought there might be a few spectators there to see us off. Not a bit of it. In fact, there were more seals playing in the water about us than there were people on the quay. Apart from the longshoremen, the only onlooker was a lady with two children. She cut a rather forlorn figure and the way they lingered made me realize that they must have someone special on the ship.

When Shackleton slipped his lines at the West India Docks, London, on 1 August 1914, there were quite a few people there to see him off, as well as a lone piper playing ‘The Wearing o’ the Green’ which (and I don’t recall anybody having noticed this before) was the song they were playing on the ship’s gramophone when the ice delivered the coup that finished her by ripping aside her rudder post.

Interestingly, when the Endurance departed on the first leg of its voyage to South America, Shackleton was not on board. He followed some days later on a steamer joining them in the River Plate. By not mentioning anything of this voyage in his book South, he gives the impression that he was there. In fact, the voyage from England to South America was highly eventful: the cat, Mrs Chippy, jumped into the ocean; there was brawling in Madeira for which some of the hands were arrested and one man flogged; and while at sea some of the men got ‘mad drunk’ and one tried to throw himself over board. They even ran out of coal so that when they arrived at Montevideo they were burning the ship’s woodwork.

Some have written that Shackleton stayed behind to attend to business matters relating to the expedition. Maybe, but other researchers (most notably Huntford) have said that he had to make his peace with his wife, Emily, with whom he had quarrelled, as well as to attend to matters relating to his brother Frank who had just been released from prison for fraud.

One difference between us and the Endurance expedition is that when they unfurled their canvas and blithely sailed off for Antarctica, they did not leave a proper support organization behind them and, although they later acquired a radio receiver, they did not have a transmitter. In other words, they were unreachable. Some have speculated that this was deliberate because Shackleton knew his creditors would soon come a-knocking. We, by contrast, are in constant communication with not just our base in the UK, but also with the world. We have our phones and email and, of course, there is our website, our educational outreach programme and, finally, a sophisticated media team fronted by the television presenter Dan Snow.

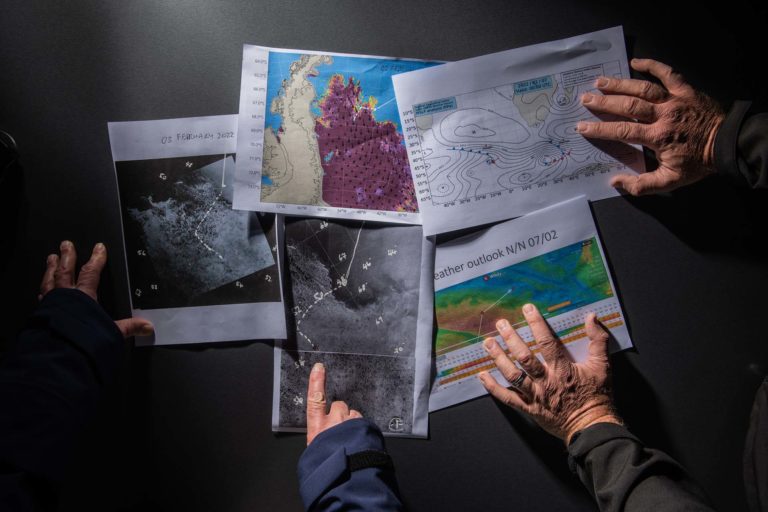

On top of this, we have a large and extremely professional support organization beneath us. This is led by the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust (FMHT), the Chairman of which (and the man at the pinnacle of the whole pyramid) is the indefatigable Donald Lamont, supported by Bill Featherstone and Saul Pitaluga. Broadly speaking the field team can be divided up into ten main divisions comprising Subsea, Science, Meteorology, Aviation, Back Deck, Medical, Engineering, Media, Educational Outreach, Sabertooth operations and Ice Camp Management. Each of these has their own support staff working out of the UK, South Africa, France, Germany, Spain and the United States. There has never before been a maritime archaeological project of this scale and complexity.

Following all the positive press we received yesterday, there has today been a tiny bit of kick-back. Predictably, some have wondered if it would not have been better to have spent our budget on Antarctic science. It’s a fair question, but it does make me smile because much the same was said when Shackleton sailed. ‘The Pole has already been discovered. What is the use of another expedition?’, questioned Winston Churchill. There were even some on the Endurance who doubted their purpose. ‘I don’t see the use of Polar exploration at all’, wrote one diarist on the day of their departure from England.

Right now we are bowling along at 16 knots. That is fast. The idea is to reach the ice edge as soon as possible so that we can maximise our search time. As I write, evening has descended but we can still make out the darkened mantle and distinctive flat top of Table Mountain with its city lights below. The sea is calm, the air is warm and everybody is cheerful. An hour ago we counted five breaching humpback whales. They ignored us completely; too busy bubble feeding and getting on with their lives.

Mensun Bound (Director of Exploration)