First full day back on the Agulhas II.

John and I have the same cabins we had back in 2019. I say ‘cabins’ but actually they are well-appointed suites with sofas, tables, swivel chairs and a long desk which supports televisions, DVD players, computers and printers. But, above all, they have two large square ports that overlook the front and side of the ship. From these I can not only look down on the stevedores as they on-load our equipment, but also the crew as they manage its stowage within the hold and about the foredeck.

After breakfast John and I went up on the bridge for our first meeting with Captains Knowledge Bengu and Freddie Ligthelm. Knowledge and Freddie are old friends, we have spent a lot of time with them on the bridge of this ship. Knowledge, the ship’s Master, is from Durban; Freddie, the Ice Pilot, is from Cape Town. On and off they have been working with each other for years. I asked what they had last been doing. Knowledge has just come back from the Antarctic on the Agulhas while Freddie has recently completed a stint as the Master of the cruise ship Silver Cloud out of Puerto Williams, Chile, which curiously enough was in the Falklands several weeks ago when I was there. ‘Good to be back?’ I asked. ‘Definitely’, said Freddie. ‘We have unfinished business’, added Knowledge.

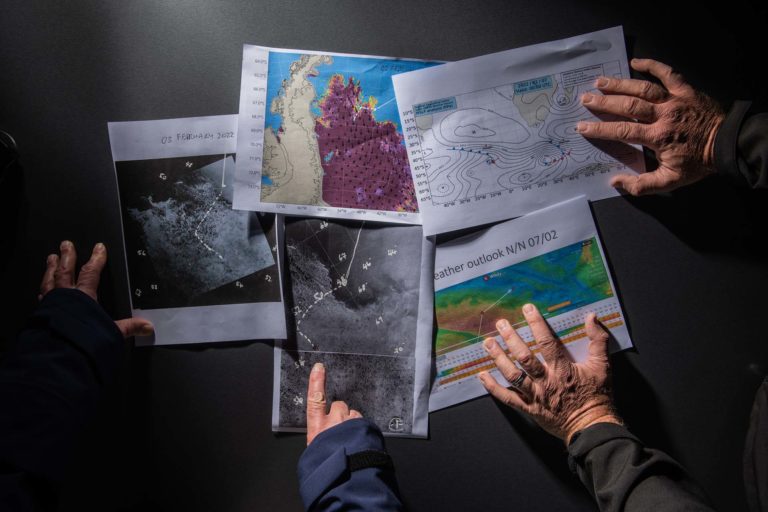

After the meeting Freddie and I looked at the latest satellite reconnaissance of the Weddell Sea. It was something we used to do every couple of days during the last expedition. The pack is not the solid fist of ice that most people think it to be. It is constantly on the move; leads (or channels) are always opening and closing and the floes are forever mutating. Although ice-coverage is densest at the centre where the Endurance is located, we are hopeful that we might find ways through the outskirts that will take us to within, say, 50- 80 nautical miles of the search area. At present there are a couple of approaches. One from the west, and the other from the east. As Shackleton used to say, there is no such thing as a straight line when you are navigating ice.

Freddie is particularly interested in a giant tabular iceberg that calved from the Larsen D iceshelf last June. Designated A-69, it is 19 nautical miles long with a maximum width of 10 n.mi. Freddie is a little concerned because, like me, he remembers its predecessor, A-68 (175 km long, 50 km wide), which actually compromised our science programme three years ago. A-69 is currently about 200 n. mi. SSW of our search box and may well be grounded (i.e. have its keel in the mud), so I do not really see it as a threat but, because it will be heading in a northerly direction, we will nonetheless keep a weather eye on it. Tomorrow we will be joined from Germany by Chief Scientist, Lasse Rabenstein. He is a sea ice specialist who has been monitoring the situation in the Weddell Sea for the Trust since November. It will be interesting to have his take on what is happening with the pack.

After leaving Freddie I went for a walk around the vessel. Nothing much has changed except for some more pictures on the walls and a new lick of paint. The big difference of course is that Covid now stalks the corridors of this ship like some black-mantled, befanged old vampire in search of blood. Our whole vessel is treated as a bubble, nobody comes up the gangway unless they have been swabbed in a little unit on dockside. Every morning we all test ourselves and then record the results on a tick-box sheet on the wall as we head into breakfast where we sit apart. We try to stay in our cabins as much as possible and when we go out we are fully masked. I find it absolutely stifling. I asked our doctor, Lucy Coulter, how long she expects us to wear these once we put to sea. ‘Oh’, she said rather breezily, ‘about two weeks’. I did some rapid-fire calculations and work out that by then we will be on site. Jolly.

Highlight of the day? Undoubtedly the arrival of the first of our two helicopters, a Bell 412. At about 1530 hours, with Table Mountain as its backdrop, we all watched as it swooped in towards us. As it came in to land it paused above us as if for effect – whop-whop-whop – and then, like lips to lips, it landed with a kiss upon our helideck. Perfect.

We have a media team of seven on board. One of their objectives is to make what Director Natalie Hewit calls an ‘observational’ style documentary. By which I think she means just quietly watching people at work while talking to them about what they are doing and what’s happening within their fields of speciality.

Today, for instance, they filmed me unpacking. In particular they were interested in two of the charts I had brought with me in a tube. One of them was the famous Admiralty Chart 4024 which covers the Falklands, South Georgia and the Weddell Sea. I pointed out to Natalie that what I liked about this chart is that, for the area within the armpit of the Antarctic Peninsula where we are heading, there is nothing. All the seabed contour lines suddenly cease and it is completely blank. Nada, zilch, diddly-squat. In other words, this whole area has not been surveyed; from a hydrographic point of view it is terra incognita. It is where the map ends. It is where the Endurance sank.

Put another way, when we enter the pack we are going off the map.

You know, I find it really remarkable that we have recorded every feature of the moon in tiny detail, we have a lander on Mars probing the planet’s subsurface and, as for Voyager One, it is now out there in interstellar space transmitting data from beyond the Kuiper Belt. Indeed, we know more about the rings of Saturn than we know about our own Southern Oceans. To me it is painfully paradoxical that we can peer 32 billion lightyears across the observable universe, but we cannot see to the bottom of the Weddell Sea.

Oh, almost forgot. I said there was a second chart. Well, I am all blogged out, so I’ll get to that tomorrow.

Mensun Bound (Director of Exploration)