The ship is an absolute hive of activity. Crew, team and subcontractors, all in orange coveralls, white hard hats and black metal-capped boots are to be seen everywhere. Work-station containers are being winched onto the afterdeck, many tons of polar-diesel and Jet A1 helicopter fuel are going into Cargo Hold 3 and, above the bridge, Satcom antennae are being installed which, we are promised, will give us ‘good on-the-move connectivity’. And then there is all the noise; the constant hammering, the crackle of hand-held radios, running motors of all kinds and the weird hissing that welders make when they are burning metal. And finally, punctuating it all, is the ship’s intercom which periodically pings to life with instructions from the bridge (‘Now hear this, now hear this … we are pumping fuel. All smoking and hot-work to cease.’). And so on. In three days everything has to be loaded, lashed and stowed for sea. It is all about good organization and forgetting nothing; if we are going to succeed not a single trouser button can be missing.

Almost all the team are now on board. One of the new ones to arrive came by my cabin. His name is Tim Jacob. He fronts an organization called Reach the World that is based in New York. His remit is to take us into classrooms around the globe so that John and I and the other specialists on board can talk directly to the students, answer their questions and, in our own stumbly-bumbly way, try to inspire them to go out and attempt big things of their own.

I have worked with Tim before, he is a natural teacher, the kids love him. He is also a Shackleton enthusiast of the swivel-eyed, card-carrying, copper-bottomed kind who, before he had even accepted my offer of a coffee, had launched into a homily on William ‘Bakie’ Bakewell, one of the lesser-known figures (and only American) on the Endurance. 40 minutes later as he stood up to leave he asserted, averred and avouched that we were ‘writing the final chapter of the Shackleton story.’ Good one, I thought, and scribbled it into a notebook so I wouldn’t forget it.

Talking of Shackleton, I said yesterday that I would today discuss the second chart on my wall.

One of the joys of this whole endeavour has been getting to know some of the descendants of the Shackleton family. Last August I met Pippa and Roderick Wordie over the internet and later my wife, Jo, and I had a delightful lunch with them at a restaurant in the Cotswolds. Pippa and Roderick are the grandchildren of James Wordie who was the geologist on the Endurance. In terms of who he was and what he achieved, he was clearly one of the most admirable people on the expedition. In later life he became head of a Cambridge college, President of the Royal Geographical Society and a founder member of the Scott Polar Research Institute. Meticulous, enquiring, disciplined, he was a scientist to his Scottish finger tips, so it is not entirely surprising that he was the one who made the famous drift map of the Endurance.

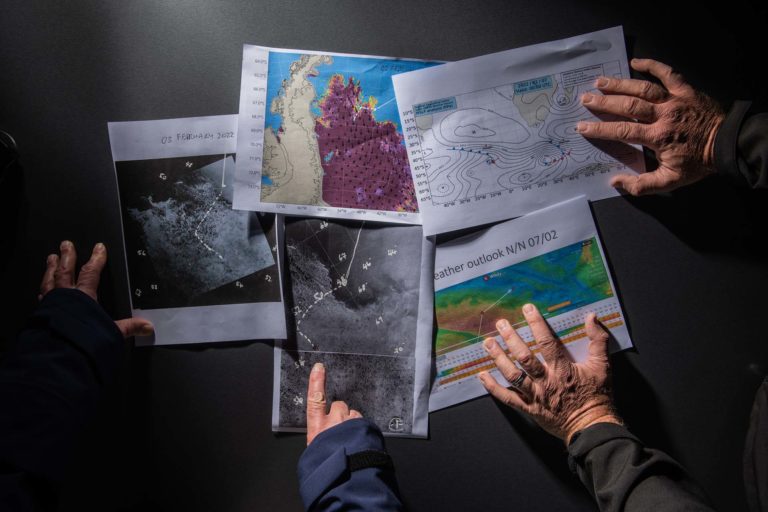

I say map, but it is much more than a map; it tells the story of a broken ship upon a sea of daggers. It starts on 18 January, 1915, when the Endurance became icebound. You can then follow its progress down to its furthest South of 76⁰ 58’ and then its zig-zag route as it is carried north on the gyre to where it sank. Thereafter one can trace the drift of the men on the floes until 9 April, 1916, when they took to their boats and, six days later, made Elephant Island. It tells a story that is, ultimately, one of hope, determination and survival, but it is also a cautionary tale. A warning that seems to say, ‘if you sail my icy main and presume upon my frozen core, I may crush you like a bug.’ Occasionally in 2019, the more nervous of nature asked if they were safe in this ship. I always respond in the affirmative, but when I look at the satellite data and I see giant floes that weigh millions of tons I cannot help but wonder what would happen if, let’s say, we got caught in a Force 10 and were nipped between two of them.

Anyway, the day before I left to join the ship a package turned up on my doorstep from Pippa. Inside was a picture of her grandfather, a photo of the Endurance slumped over in the ice with a worried looking Shackleton gazing out over the pack, and, between two sheets of cellophane, a copy of Wordie’s drift chart. They are all on my wall.

Mensun Bound (Director of Exploration)